Improv Basics: Story Spine

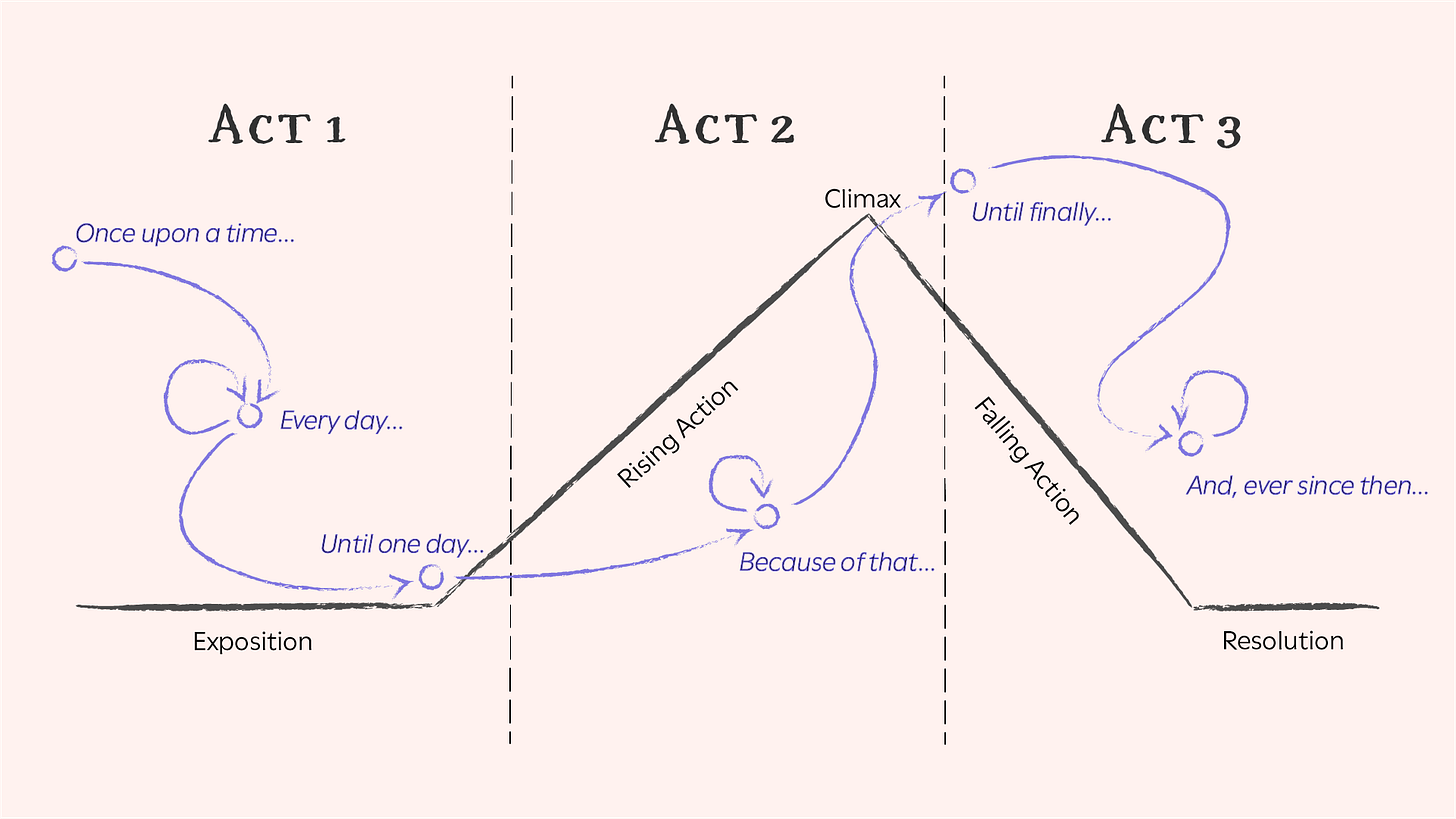

You have probably seen Freytag’s Pyramid in English class. It looks like an inverted V with a flat region on either side. Perhaps you used it to outline a story before writing it. Unfortunately, this process is useless in improv since you can’t start with an outline of the scene; however, we still want improvised stories to follow this structure. Kenn Adams’s Story Spine1 is a great tool to understand how.

A playwright might start with a main idea, turn it into a plot diagram, outline specific scenes, and then start fleshing out the dialogue (not necessarily starting with the first scene). This is known as a “top-down” approach because you can imagine each stage of this process as a level of a pyramid, starting from a single idea and expanding into the complete story. In an improvised story, we must instead tell the story linearly. The linear analog of the plot diagram is the story spine.

You can outline a story as follows:

Once upon a time…

Every day…

Until one day…

Because of That…

Until Finally…

And ever since then…

(optionally) And the moral of the story is…

Exercise 1: Take a popular movie that everyone in the class knows. Map it out with the story spine together. Then have them do it with a different movie in small groups.

Example (Star Wars): Once upon a time, there was a boy named Luke Skywalker who lived with his aunt and uncle on Tatooine. Every day, he worked on the moisture farm. Until one day, he encountered a droid with a secret message. Because of that, he meets Obi-Wan Kenobi and learns about the Jedi. Because of that, he needs to deliver the message to Alderaan. Because of that, he meets Han Solo, who has a spaceship. Because of that…. Until finally, Luke blows up the Death Star. And ever since that day, the galaxy was safe (until the sequel, anyhow).

Since Kenn Adams invented the story spine in 1991, it has become very popular. Pixar famously used it to write many of their films. For improvisers, it provides a nice fill-in-the-blank approach to storytelling. Within a scene, you only need to know where in the story spine we are, and the structure tells you what should happen next.

Exercise 2: In a circle, go around the room improvising a story one sentence at a time. Start each sentence with one of the phrases from the story spine. Encourage students not to overthink it. Usually, they will find that relying on the story spine takes away some of the cognitive load when improvising a story. Because the story spine starts with “once upon a time,” these stories tend to sound like fairy tales; nevertheless, the structure works for any genre.

The Three-Act Structure

The story spine approach fits nicely with the three-act structure, and I’ll use the two interchangeably when directing improv. The way I think about it is that there are three main sections of the story spine:

Act I: Every day…

Act II: Because of that…

Act III: Ever since then…

Each of these can appear multiple times in the story spine. The remaining story spine elements are simply the divisions between acts, and they can only appear once in the story.

“Once upon a time…” is the beginning of the story. A story cannot have multiple beginnings.

“Until one day…” is the inciting incident. Having more than one can make the story feel messy and lacking focus.

“Until finally…” is when the problem is finally resolved. This moment must feel earned. If there is more than one of these, then it feels like an overly convenient coincidence (i.e., a deus ex machina).

I’m not recommending that anyone think about all this theory during improv. Ultimately the goal is to be able to follow this structure on instinct. You must practice so you know what an Act I scene feels like. It feels different from an Act II scene, which feels different from an Act III scene. Also, you must identify the transition points between the acts. Noticing these transitions can be the hardest part because these events must be clear to everyone on stage. If one player sets up a tilt and another player doesn’t treat it as such, then the plot gets confusing with one player heightening while another continues giving exposition.

Improvising an Act I scene is all about saying “and.” What else is true? You must fill the world with details that will serve as the platform for the rest of the story. In a narrative, we must understand our protagonist(s) and their wants. They need to feel like three-dimensional characters before we move on to Act II. The transition between Act I and Act II is called the inciting incident, “the tilt,” the crossing of the threshold, and the point of no return. Identifying this moment is very important and thus deserves its own article (see Platform, Tilt).

Improvising an Act II scene is all about saying “but” and “so.” The characters keep encountering obstacles (“but”s) and they must find solutions (“so”s). Act II is all about coming up with reasons why the problem cannot be solved yet. In narrative shows I’ve directed, often the rule has been that the players cannot solve the main problem until they get a bump from the tech booth indicating we only have 10 minutes left (of our hour-long show). At that point, the next thing the protagonists try always works perfectly, no matter how ridiculous. Usually, the transition between Acts II and III is just based on the pacing of the show, but it needs to be clear to the whole cast. Once Act II is over, there can be no more “but”s.

An Act III scene is about tying up loose ends. What questions are left unanswered? What do we hope to see? If the first two acts have gone well, Act III is incredibly easy because it is natural to want to resolve things. If Act III is not going well, the problem is almost always in the first two acts.

For a Single Scene

The story spine is easiest to analyze in the context of a narrative, but a scene can tell a story in itself. Thus, the story spine applies there as well.2 Act I is all about establishing the base reality (see CROW), which then culminates in a tilt (see Platform, Tilt). In Act II, we heighten the stakes (see What of the Scene). Sometimes, the scene ends there though. Many scenes (especially in sketch writing) do not have a third act, and that is okay. When there is a third act, it can take many forms, but it serves to put a cap on the joke or the story of the scene.

You can use whatever story structure works best for your brain—story spine, plot diagram, story circle, etc.—and none should be taken too strictly; nevertheless, these aspects of plot should eventually become innate, especially for narrative improv.

Kenn Adams has a great article on it here. For a more in-depth explanation, I recommend his book, How to Improvise a Full-Length Play, The Art of Spontaneous Theater. It’s a good read for anyone interested in learning or teaching narrative improv.

Stories have somewhat of a fractal structure. A series tells an overarching story, made up of books, made up of chapters, made up of scenes. I’m sure someone could make an argument that it applies to sentences too, but that goes beyond the point of usefulness.