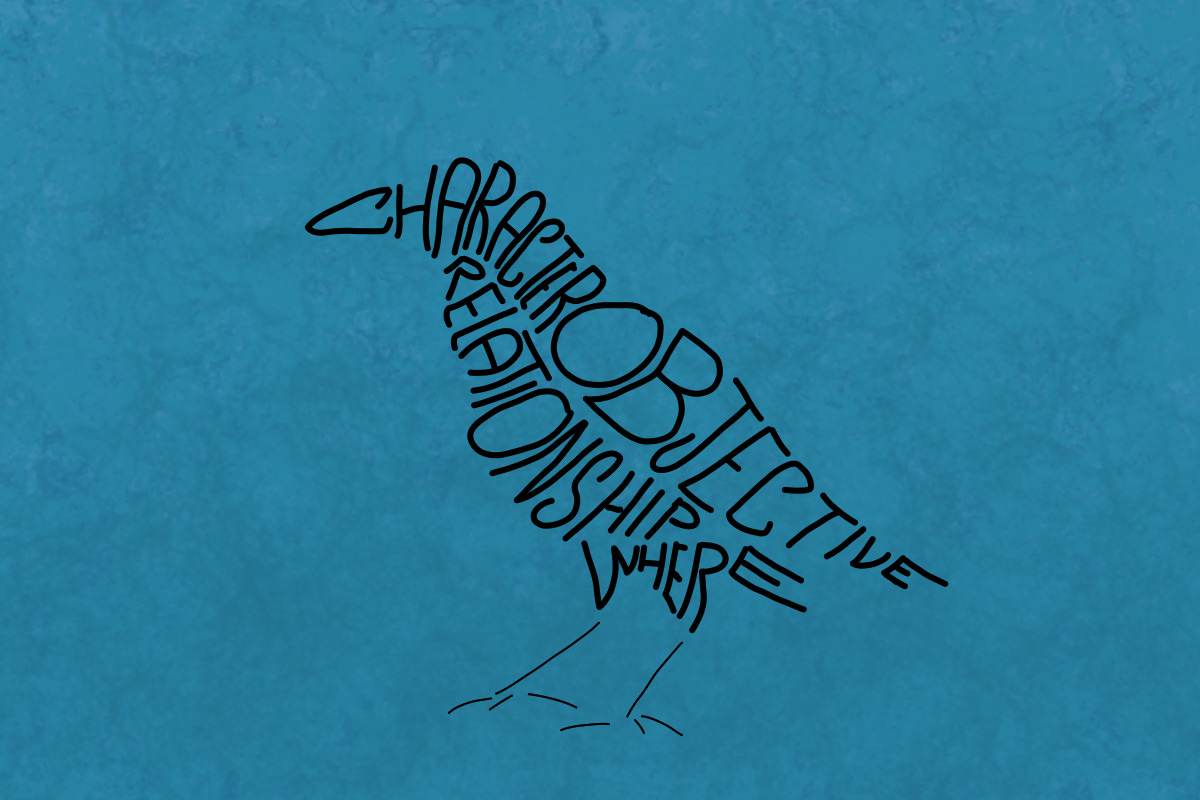

People who have never done improv before have still heard a lot of the basics, like “yes, and.” CROW is probably the first topic in the curriculum that is brand new information for most students; however, it is fundamental to good improv.1 CROW is a checklist of sorts. It is the four things that need to be established in every improv scene, preferably very early in the scene.

In a good improv scene, there’s a moment where it becomes easy. What comes next seems obvious. If it’s not and you feel stuck, then a likely culprit is that you are missing one or more elements of CROW:

Character: Also called “the who of the scene.” Who are these people on stage? Ideally, give them names. We also want to know what type of people they are. How old are they? What is their attitude (in life and in this moment)? Do they have an interesting voice? Do they have a unique physicality? What do they do for work? What do they do for fun? What are their hopes and dreams? We don’t need the answers to all these questions, but we need enough. It’s hard to say exactly what “enough” is—it depends on the scene—but consider, if you saw this character later in the show, would you be able to recognize them as the same person?

Relationship: What is the relationship between the characters? Specifically, it must be between the characters currently on the stage. Relationships with external characters can be established later. We need to know how the characters we are currently watching relate to each other. E.g. siblings, roommates, best friends, a parent and their child, a therapist and their client, an assassin and their target. Then go deeper. Saying that you’re siblings is just establishing the bare minimum. Who is older? Do you get along or do you not like seeing each other? How has your relationship changed from when you were younger? The more specific you can be about the relationship, the easier it is to do the rest of the scene. All stories are about how relationships change over time.

Objective: This is perhaps the hardest of the four to explain. It is the “what of the scene”, and probably deserves its own article. In short, there are two ways of thinking about objective. The first is the current objective of the characters. If they are in the woods, why are they there? Are they looking for something? Are they hiking and are just trying to relax? If that’s just where they live, what chores are they up to at the moment? The objective is usually not just to have a conversation. If it is, it’s probably a specific type of conversation—a date, an interview, an intervention, etc. The second part of objective is the objective of the scene itself. If there’s a story happening, what is the story arc? If there’s a game to the scene, what is the premise?

Where (and When): This one is the same in CROW and “Who What Where”. It makes the acronym work, though it sort of breaks the pattern. Some folks prefer “Environment” instead, making the acronym CORE. In either case, this is the location for the scene, (not just in space, but also in time). It’s probably the most overlooked element of CROW. We want to know where the scene is taking place in general (e.g., amusement park, grocery store, farmers market, etc.), but we also want to know how that reality fits on the stage. Try to establish where things are on the stage. Use space work. If you establish there is a coffee table in the middle of the stage, and then later, someone walks around the imaginary coffee table, the crowd goes wild every time.

When to get CROW out? Some people will say you should establish all parts of CROW within the first three lines of the scene. This efficiency is certainly a good skill to have; however, it can lead to some clunky scene starts. “Hey Tom, as your brother, Chris, I am so glad we’re here at the science museum on a Tuesday morning to learn about dinosaurs.” If every scene starts like that, it can get stale. Nevertheless, CROW should still come quite early in the scene.

Take inventory a few lines into the scene. Especially if the scene feels like it hasn’t clicked yet, run through CROW in your head. If something is missing, try to fill in those details. I often do this exercise in my Level 2 classes. I give students three lines in a scene and then call freeze. Then we, run through CROW and see parts are missing. After I call unfreeze, the students have a couple more lines to fill in the details. After some practice, it becomes very easy to identify which parts of CROW are missing from within a scene, and the eventual goal is for that inventory-taking to become subconscious. After you’ve been doing improv for some time, a scene that is missing CROW will just feel like it’s missing something and you’ll add in those missing details on instinct.

Also check out Lloydie James Lloyd’s alternative to “who, what, where” called “emotion, relationship, situation.” I love it. It’s an easy way to get to all the deeper parts of CROW I was trying to explain above. Read his article on it (and follow his blog too!):

CROW is a regionalism. Some people prefer a different acronym or mnemonic. It doesn’t really matter which one you use, but I was taught CROW, so that’s how it lives in my brain.