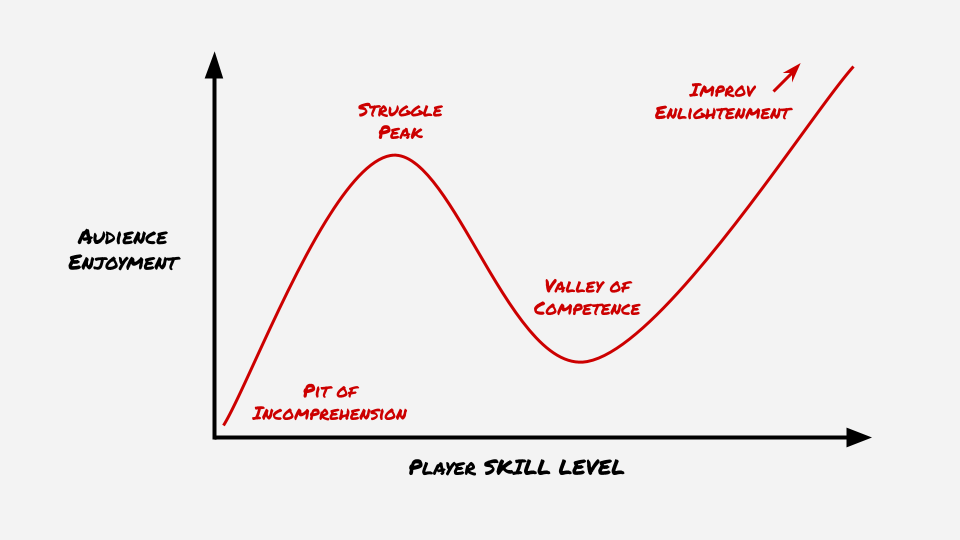

The difficulty curve of many short-form games looks like this:

This graph applies to the type of games with a strong gimmick. Examples are the Alphabet Game, a Word Restriction Game, or Foreign Film Dub. All of these games involve a complex rule that the players must follow throughout the scene.

In the bottom left region, the game is too hard, and you are just trying to escape the Pit of Incomprehension. Just following the rules takes up too much brainpower and the scene doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. After practicing the game a few times, the gimmick doesn’t get in the way anymore, and you can even start to use the gimmick in fun and interesting ways. For example, the audience loves seeing how players are going to deal with the more difficult letters of the alphabet in the Alphabet Game. The moments where the performers genuinely struggle are fun for the audience.

As you continue to improve, there are diminishing returns. Remember that the audience doesn't know how hard the game actually is, because they've probably never tried to do it themselves. If you get too good, you can make it look easy, and at this point, the gimmick loses its potency. Seeing a player be really good at remembering the alphabet is not as fun as seeing them frantically trying to think of the next letter. This is the Valley of Competence. Here are the three options to deal with it from worst to best:

Make it look hard. You can intentionally mess up or struggle with the game. You might be able to get away with it a little bit, but it's dishonest. The audience will see through it eventually, and you'll lose a bit of their trust. (See The Second Show Must be Honest).

Actually make it hard. Find a way to make it harder for yourself. Most of the time, you can accomplish this by just going faster. The audience doesn't know how the game is usually played, so you can impose more restrictions on yourself. A director or ref can help with this as well. If players are too good at the Alphabet Game, I might tell them to start going backwards through the alphabet. This gets an “ooh" from the audience, and it usually trips people up a bit. This strategy is a good option if the next option doesn't seem feasible in the moment.

Push past the valley. There is a region beyond it, and this is the true goal of the scene. In this region, you can use the gimmick well enough, but it is not the focus of the scene. Scenes that live in this region are about relationships that can be meaningful despite the gimmick. You establish games in the scene that are unrelated to the gimmick. These scenes transcend the limitations of the format to be fulfilling scenes in their own right.

Never ignore the gimmick. The scenes that surpass the valley aren’t scenes that are ignoring the gimmick of the scene. If you are playing the Alphabet Game, you must follow the rules for the whole scene. You can’t just come up with some trick that allows you to not play the game. The audience will turn on you. Scenes beyond the valley are scenes that demonstrate a mastery of the gimmick. They overdeliver on it.

Not every scene should be beyond the valley. A good short form show will have a mix of scenes on either side of the valley. If there are no games in your set that genuinely challenge the players, you need to play some different games or invent brand new ones. If you don’t like being on Struggle Peak, then perhaps short form improv isn’t the right format for you.

Games that are too gimmicky can only excel on Struggle Peak. The valley is to expansive to traverse. There are some short form games that I dislike because, I’ve never seen them go well—or more specifically, the only times they go well is when it’s delightful to see the players struggle with the mechanics. In a good short form game (according to me), the region beyond the valley is attainable, but challenging to reach.

When I’m teaching, this graph informs how I give notes in the early levels versus later levels. At first, I just want my students to be able to consistently make it up the mountain. No matter what the rules of the scene are, they should be able to consistently make a scene that at least makes sense and to find joy in failing to follow the rules perfectly. Then, in the later levels, we focus on making it past the valley.